Conor, one of our sons, was 9 years old when he was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes (T1D), an autoimmune disease that leaves patients unable to regulate their blood sugar levels without giving themselves tightly controlled doses of insulin. Looking back at the weeks prior to his diagnosis, we had noticed some changes in his behavior that we attributed to a variety of other causes. For instance, his appetite had noticeably increased and he seemed to be constantly hungry, even after finishing a meal. But despite this, he had actually lost 10 pounds, and since he was thin for his age, he really couldn’t afford to lose that weight. We thought he was just going through some sort of unusual growth spurt and would surely be growing any day now. He had also been using the bathroom with urgency and drinking a lot more than usual — he seemed constantly thirsty. But since this was summer in Florida, we thought he must have simply been rehydrating often, something Florida parents usually tell their children to do during the summer. Conor has some other health conditions that affect his muscle strength and stamina, so we thought his symptoms could be related to that as well. We have no family history of T1D so we were not thinking “diabetes.” The day before his T1D diagnosis that June, Conor played in a baseball game. It was the last game of the season, and he said he didn’t want to play. We didn’t want him to quit and he wasn’t really “sick” — no fever, vomiting, etc. So we persuaded him to play, telling him it was the last game and that his team needed him. Again, it was a hot summer day, but he seemed unusually tired, even having difficulty at times swinging the bat with any force. We still thought these were effects from his other medical conditions combined with the heat, but things seemed to have gotten worse. I’m a nurse and had learned the signs of T1D, but I feel that sometimes health care providers can be less cautious when health issues arise with their own children, not wanting to sound an alarm if it’s nothing. I finally asked a friend, who is also a nurse, and she said, “You need to take him in, something is wrong.” We were seen in the after hour’s clinic that evening. When they checked his blood sugar and the meter simply read “High,” I knew that meant Conor’s diagnosis would be Type 1 diabetes. The normal fasting blood sugar range is 70–100 mg/dl while a reading of “High” usually means the blood sugar is over 600 mg/dl. My mind immediately imagined worst cases scenarios for my son’s future from what I had witnessed in my nursing career: blindness, kidney failure and amputations. Later in the hospital, the laboratory blood sample registered a blood sugar level of 848 mg/dl. Conor’s life and our family’s life had changed forever.

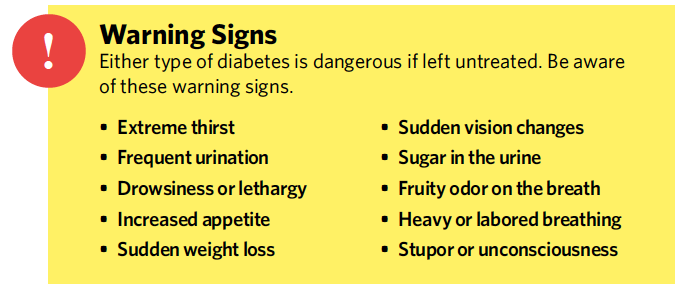

We were quickly admitted to UF Health Shands and introduced to the amazing team of doctors, nurses and diabetes educators in the Pediatric Endocrinology Department — people who would become part of our extended family. We were immediately plunged into what seemed like another world, one dictated by blood sugar levels, counting every carbohydrate consumed and insulin injections. Conor is the second oldest of our four boys and is, of course, the most averse to needles. This, on top of raising four boys with both my husband and myself working full time, was going to be a challenge! But with the support of our new family members (the Endocrine staff), we started the learning process. We gave ourselves saline injections with the same small needles used for insulin injections so we would know that it wasn’t as bad as we were imagining. And it wasn’t. We learned about the signs to look for with high blood sugar, most of which we’d already seen before Conor’s diagnosis. We learned about the dangers of low blood sugar, including coma, seizures and death, as well as how to treat it. Candy and juice were now medicine, which caught Conor’s attention! I was very familiar with all of this, having been an ICU nurse, but it had never been this close to home before.

After a four-day hospital stay and rigorous training, we were able to go home. But honestly, it was almost like bringing home a newborn for the first time. We were exhausted, anxious and uncertain. T1D is a 24/7/365 job with no breaks. Conor required six to eight injections of insulin per day, numerous finger sticks for blood sugar checks and carbohydrate counts for everything he ate and drank. We downloaded phone apps to assist in the carb counting. My husband and I took turns waking up at 2 a.m. every night to sneak into Conor’s room and check his blood sugar because we were terrified of the nighttime low we had been warned about.

When most people hear the word “diabetes,” they picture a person who may be overweight, eats too many sweets, or both, and has to take insulin because of their diet. This is Type 2 diabetes, which is the more common form. According to Mayo Clinic, Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease in which a person’s pancreas stops producing insulin, a hormone people need to get energy from food. This differs from Type 2 diabetes, in which the body resists the effects of insulin or doesn’t produce enough to maintain a normal glucose level.

Though Conor has Type 1 diabetes, many people still ask if he can have juice, candy or other sweets. And the short answer is “yes.” People with T1D can eat anything. But since their pancreas can no longer regulate their blood sugar levels by making sufficient amounts of insulin, people with T1D must administer the right amount of insulin for the amount of carbohydrates they consume. They must take over the function of their damaged pancreas. So when one of his classmates has a birthday and brings in cupcakes to share with the class, Conor can enjoy one, as long as the carbs are entered into his insulin pump. I recently saw a T-shirt that summed up this point perfectly: “What should people with Type 1 Diabetes NOT eat? POISON … or anything that contains poison.” Unfortunately, the number of people diagnosed with T1D every year is increasing. Therefore, it is important to recognize the signs and symptoms and seek medical attention.

His diagnosis came during the last week of school, making it challenging to find child care during the summer. We were just learning how to cope with our new lifestyle and had to train others to take care of him so we could be at work. There are not many programs that have a nurse available for summer camp. Luckily, our children’s school, St. Patrick Interparish School, was willing to learn to give injections, check blood sugar and count carbs. They learned what to do in an emergency and called us immediately with any questions/concerns. They knew Conor and our family, so it was such a relief to have him there. Conor was also encouraged to go to Florida Diabetes Camp three weeks after his diagnosis. This was a great opportunity for him to be around others of varied ages at different stages of diagnosis. He learned to check his own sugar, give himself insulin shots and to count carbs. The counselors and staff of the camp were amazing. He went back the next year as well, and it was a “diabetes vacation” for us as well. The next school year, his teacher, Mrs. Milliken, was very cooperative and helpful in doing what she could to accommodate Conor’s “new normal” at school.

Gainesville not only has a wonderful diabetes medical team, but also an amazing group of supportive families. I contacted the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation shortly after we returned home to gather more information. Within a day, a Gainesville mom of a child with diabetes reached out to me to give support. I joined a JDRF-sponsored social media group with her and other families living with T1D that organizes get-togethers, educational guest speakers, fundraisers for diabetes and even a place to get diabetes supplies in a pinch. They readily answer questions, provide tips, keep us up to date on the newest research progress, support local 5k races that raise money to support T1D research and disseminate other important information. We have found their support invaluable in dealing with this unpredictable disease.

Six months after diagnosis, we were fortunate to get Conor an insulin pump. This is a device about the size of a pager that delivers a small, steady insulin dose all day (basal rate). It can also calculate and deliver insulin for correcting high blood sugar and carbohydrates consumed. We just manually input how many grams of carbs in his meals and his blood glucose values. It delivers insulin through tubing and a site under the skin usually attached to his hip or stomach, which needs to be changed every three days. Another huge advance in T1D care was the continuous glucose monitor (CGM). This is another device that tracks his blood sugar every five minutes using a filament under the skin. We can check this data on our smartphones and set both high and low parameters that alert us if his sugar gets too far out of range. We have been able to get more sleep at night knowing the CGM will alert us if Conor’s sugar gets too high or too low.

With T1D, ailments that were previously only annoying now can require hospitalization. GI bugs and the flu can take away the only option we have to raise Conor’s blood sugar if it gets low — eating. And they can change the way his body responds to insulin, so much closer blood sugar monitoring is required when Conor gets sick. In addition, stress can also affect how much insulin his body needs to correct high blood sugars.

We have adopted the philosophy that it is not only Conor that has T1D, but our entire family, since diabetes truly affects the entire family. We all must be aware of the signs of high and low blood sugar and what to do in an emergency. Conor always has to carry an emergency supply of insulin and sources of sugar with him, along with his blood sugar testing supplies. Either my husband or I accompany him on field trips and scout campouts. Conor requires more attention to keep his blood sugar in a healthy range.

We have to train the teachers at the start of every school year. We educate his classmates so they understand what it means to have diabetes. My husband became a board member for JDRF. We have done several 5k runs in support of diabetes, and the entire family has entered research studies. This past year we attended the Friends For Life conference in Orlando, put on by the group Children with Diabetes. It is an international conference that has discussion groups for all ages, including siblings and family members. Up-to-date educational and research material is presented, and attendees have the opportunity to meet famous people with T1D who have gone on to do extraordinary things, such as mountain climbers, American Ninja warriors, racecar drivers and musicians. Exhibitors are available to answer questions and let you try different supplies. It was wonderful to be surrounded by other families who understand the minute-by-minute struggle that is T1D.

Looking back on our first year with diabetes, I can honestly say we are a stronger family because of T1D, not that I would wish it on anyone else. It is still a life threatening disease that has no cure, but I am grateful for the support we have received and friends we have made because of T1D. I am thankful to be in Gainesville where the T1D community has been extraordinary.

Serious Statistics

- 1.25M Americans are living with T1D including about 200,000 youth (less than 20 years old) and over a million adults (20 years old and older).

- Five million people in the U.S. are expected to have T1D by 2050, including nearly 600,000 youth.

- Between 2001 and 2009, there was a 21 percent increase in the prevalence of T1D in people under age 20.

- Annual T1D-associated healthcare costs in the U.S amount to $14 billion.

- Less than one-third of people with T1D in the U.S. are achieving target blood glucose control levels.

- T1D is associated with an estimated loss of life expectancy of up to 13 years.

How does Conor feel about all this?

After being diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, Conor spent very little time feeling sorry for himself. Of course he was unhappy that he had to get shots with every meal or snack, so he gravitated toward carb-free items like cheese sticks or deli meat to avoid having to get a shot. After going from insulin shots to an insulin pump, there was an adjustment period. The delivery device used to insert the site intimidated him at first. It has to be changed every three days and rotated around different areas on his body so as not to build up scar tissue at one site. Early on, Conor was hesitant to change his pump sites and try new spots on his body. Later, Conor was approved by our health insurance to receive a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), a device that samples his body’s sugar and sends that data to our smartphones so we can monitor him remotely. Of course, this is another site through his skin that we have to change periodically. Conor has adapted very well, and these devices sure make things easier for us all. For instance, before his insulin pump was being used he had to wait until it was convenient to give an insulin shot before he could eat his Publix cookie. Now, he just enters the carbs into his pump and enjoys the cookie at the store.

When asking Conor how he feels about having diabetes, he sums it up as a pain in the neck but a “gotta do” that he just deals with. We learned at the Friends for Life conference that there is high risk for burn out in children and teens with T1D. They simply get tired of constantly checking and thinking about their blood sugars. So to avoid this, we try to give him breaks from his diabetes. This entails us doing all the glucose checks, carb counts and insulin dosing for a certain time period. He is a typical pre-teenaged boy and gets frustrated when we continually remind him to check his sugar, ask “what’s your number?” or force him to eat all of his meal because his pump has already given him the insulin dose for those carbs. There have been occasional missteps, like when he mistakenly entered his blood sugar of 200 as grams of carbs consumed, which gave him way too much insulin. Fortunately, we caught it right away, but since the insulin had already entered his body, the fix was that he had to do what he told his pump he had done and consume 200 grams worth of carbohydrates. Break out the honey and juice!

In addition to looking and feeling better since his initial diagnosis, Conor has become more engaged, focused and has a sense of humor about his T1D. When asked about his insulin pump, he may simply say “I wear my pancreas on the outside, that’s just how I roll.” He enjoys it when we jokingly tell his brothers to count their carbs or to put 30 grams into their pumps before dinner. We are amazed at his resilience and easygoing attitude.

Related articles:

Celebrate World Diabetes Day On November 14

Learn More About Diabetes Research For National Diabetes Month

ACPS Superintendent Karen Clarke Announces Plan To Step Down

Virtual Tricks And Tips For At-Home Learning

Learn More About Pesticides: Is Our Food Safe?

Learn The Dangers Of Too Much Sugar